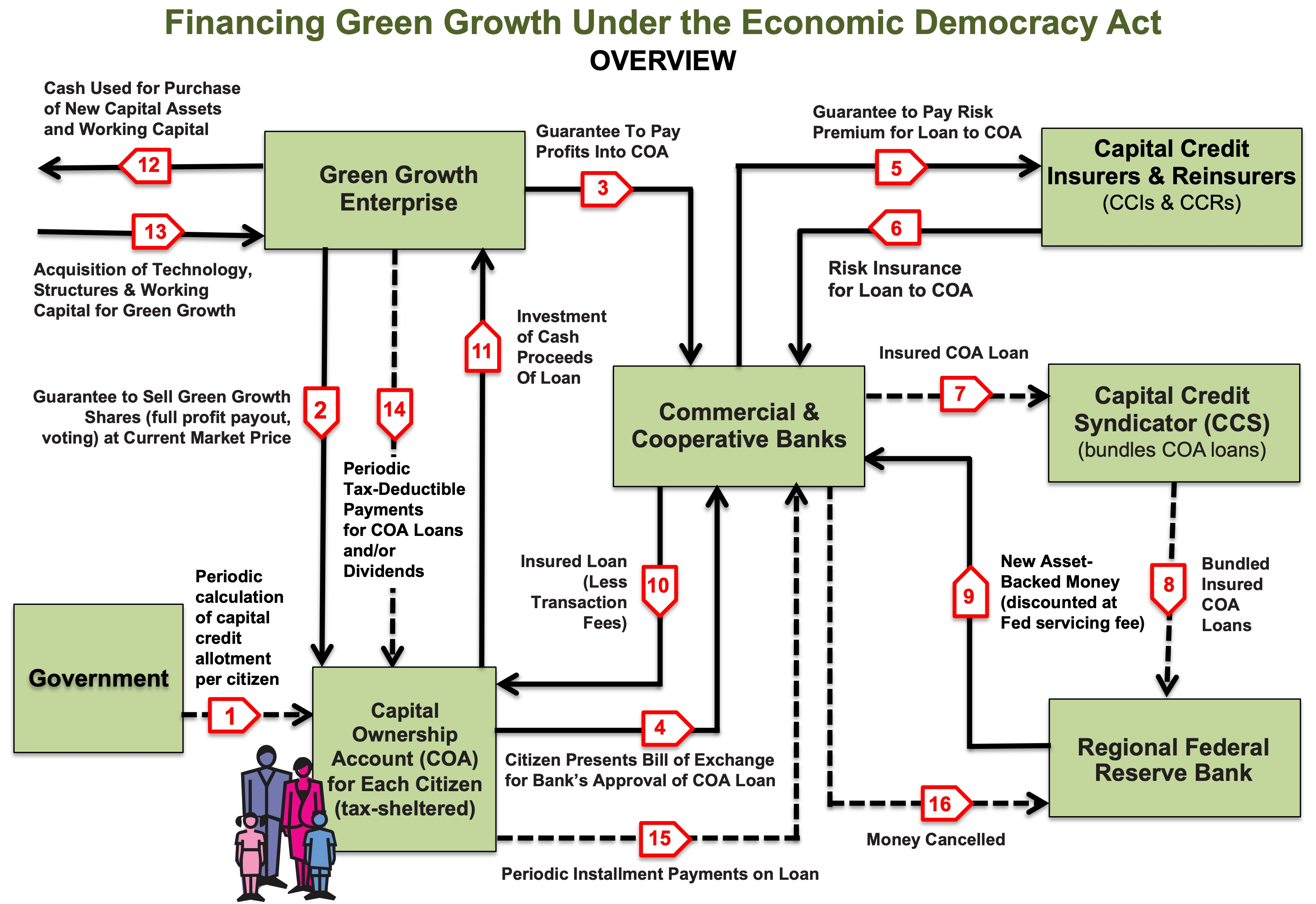

This is an overview with a step-by-step explanation of how money is created, invested and repaid under the Economic Democracy Act (formerly known as the “Capital Homestead Act”). This national program of monetary and tax reforms would enable every citizen (child, woman and man) to acquire shares in new productive capital being added to the economy each year.

Financing future capital formation and transfers this way provides businesses with equity investments to produce more goods and services to new customers who will now have an additional source of income from their capital assets. The Economic Democracy Act systematically turns non-owners into capital owners, without taking anything away from current owners.

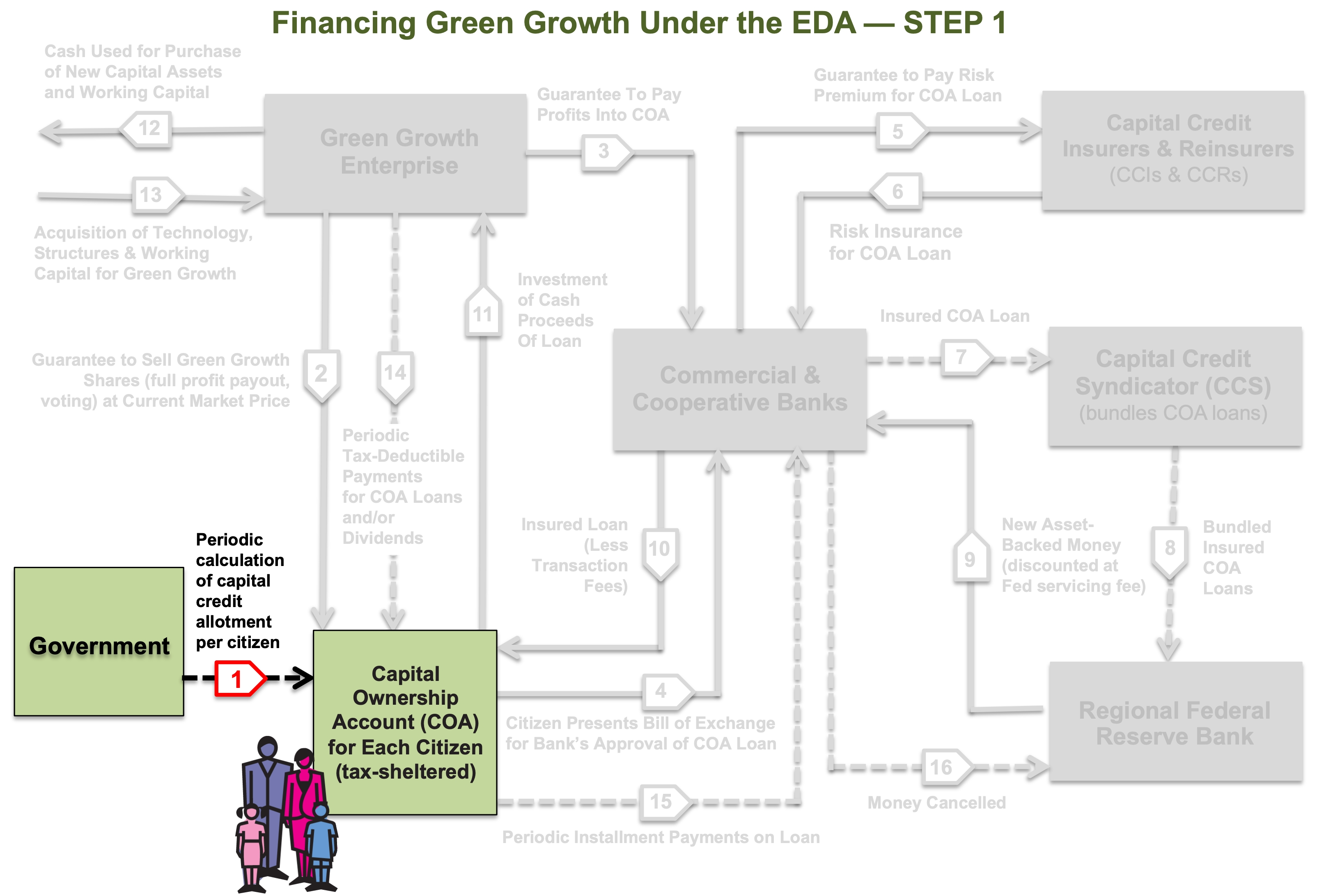

STEP 1. Each year (annually, bi-annually or quarterly) the government estimates how much productive capital will be added to the economy in the coming period, both in the private and public sectors. Dividing that number by the current number of U.S. citizens determines that period’s per-citizen allotment of interest-free capital credit.

For example, the total annual US capital formation increment for 2018 amounted to $3.955 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. When that number is divided by the total 2018 US population of 328.9 million, the result is an annual per-citizen capital credit allotment of $12,023. (For purposes of the illustration shown in “Projected Citizen Wealth Accumulations Under the Economic Democracy Act,” however, we use an annual capital credit allotment of $10,000, calculated for a slow growth economy.)

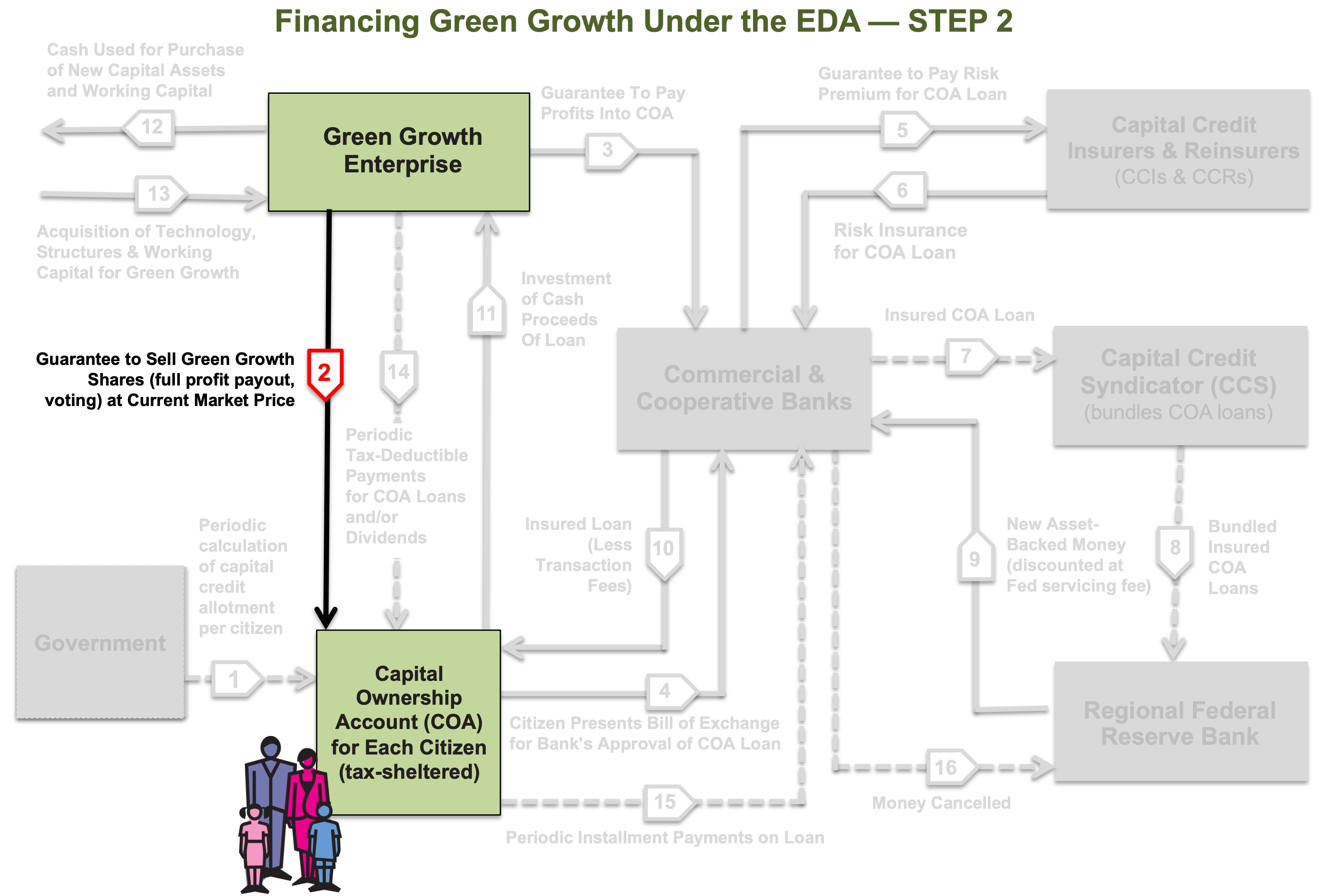

STEP 2. An enterprise that needs to finance new capital assets, such as plant, equipment, structures, patents, information technology systems, etc., decides to finance that new capital by selling newly issued shares to citizens, at their current market price. The enterprise can escape paying corporate income taxes on all full-dividend payout, voting shares. Future dividends not used to repay a Capital Ownership loan would be taxable at the personal level.

In this example a family of four goes to their local bank to set up four individual, tax-sheltered Capital Ownership Accounts (COAs). With the parents making decisions on behalf of their minor children, they will get investment advice from the bank and use their annual capital credit allotments to purchase qualified shares of the enterprise. (A portion of their capital credit allotment will be used to cover the one-time cost of capital loan insurance and bank service charges.)

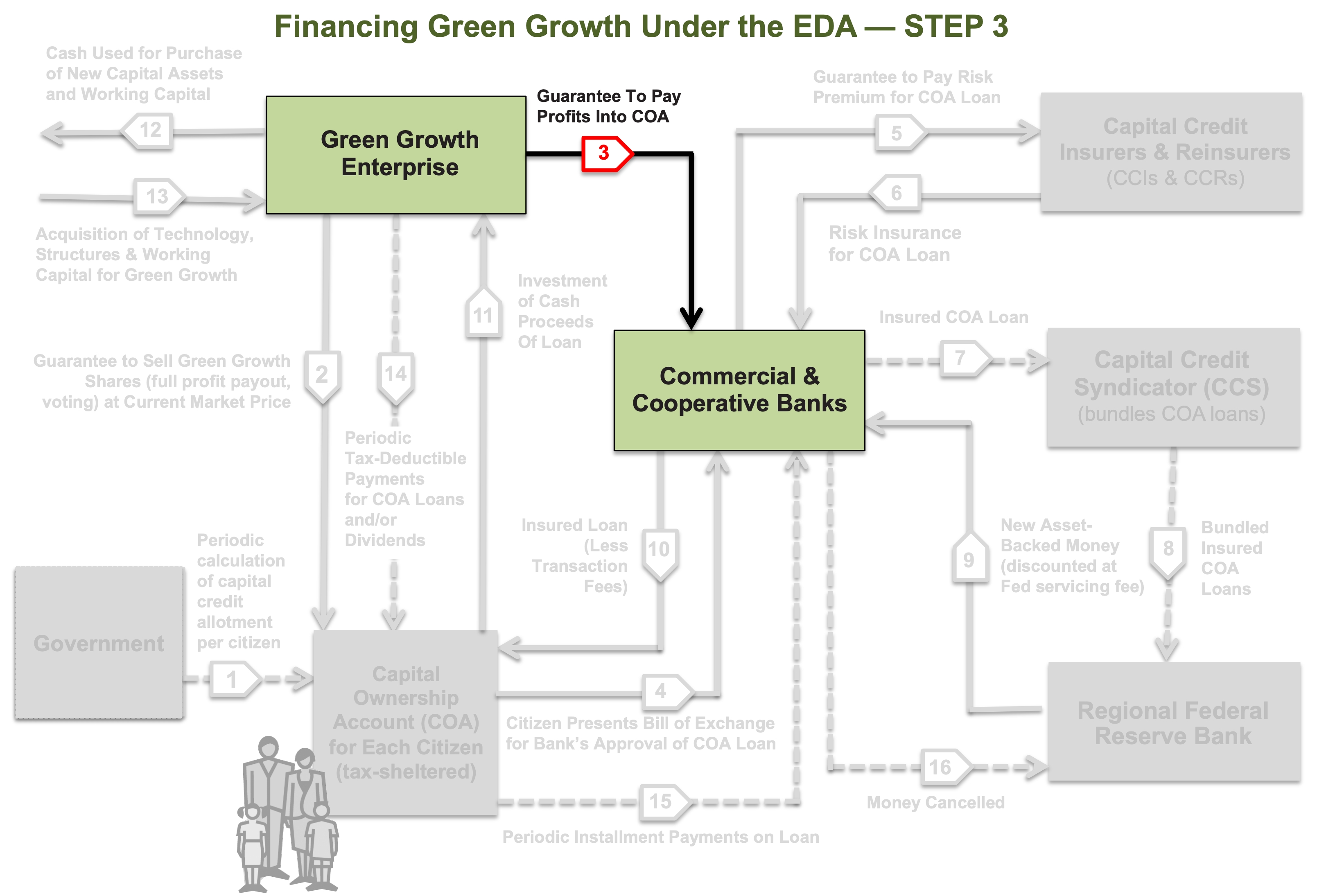

STEP 3. Under the Economic Democracy Act, the enterprise must pay annually to each citizen’s Capital Ownership Account all the profits earned on the shares to be purchased.

The initial stream of company profits will be used to pay off the scheduled COA loans. When the citizens receive dividend incomes above their periodic principal payments on their COA loans, they will be subject to personal income taxes on any additional dividends. Capital Ownership shares are tax-exempt as long as they remain in the tax-sheltered Capital Ownership Account.

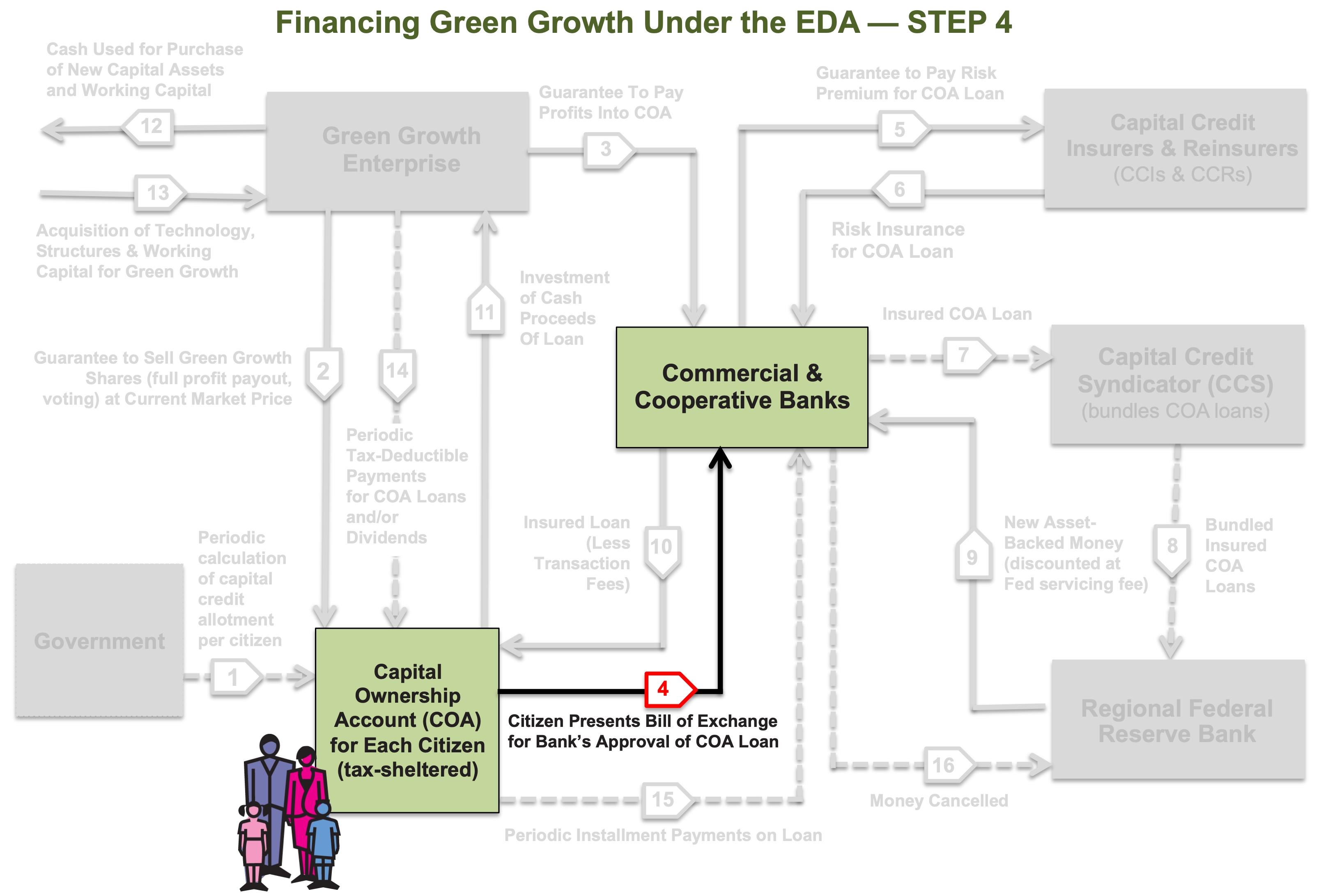

STEP 4. The family’s adults present “bills of exchange” for the bank’s approval and acceptance, in order to obtain their chosen shares for each COA loan for that period. Before the loan is made, the lender, risk insurance company and other entities will first determine the “feasibility” of each particular loan. (“Feasibility” means that the enterprise’s new capital is expected to generate enough profits to pay for itself.) Such a feasibility analysis will judge the soundness of the enterprise that needs to purchase the new capital assets, including the quality of its management and workforce, its current and future markets, etc.)

The bank in turn issues a promissory note for each Capital Ownership loan and sets up a checking account for each member of the family. In a process called “discounting” the bank will deduct from the total loan principal a one-time premium for capital credit risk insurance and service fees for the bank and other advisors.

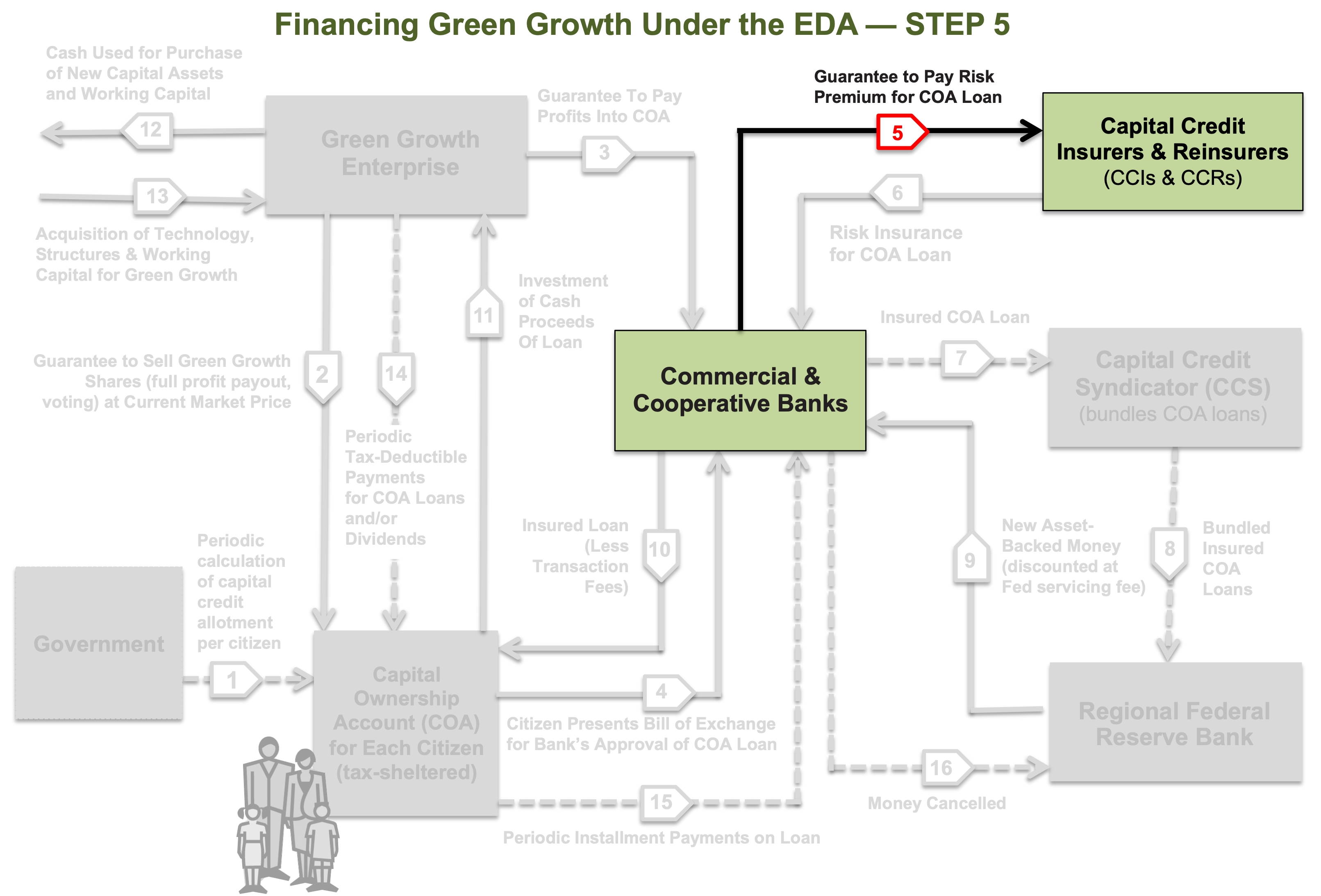

STEP 5. The bank guarantees to a Capital Credit Insurer to add a risk premium to the principal needed to purchase the shares. This premium and the bank service charges will be paid out of the COA loan discount.

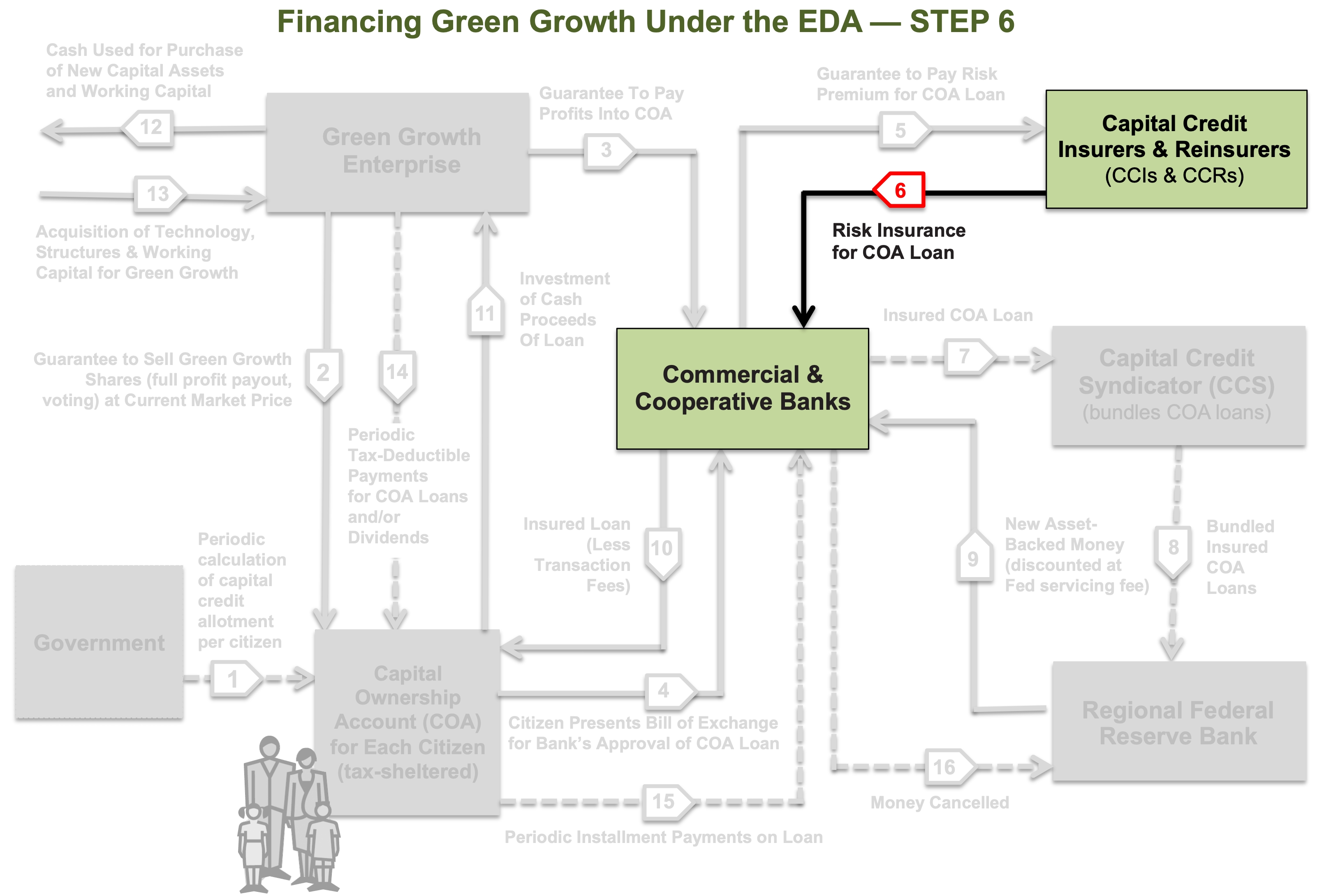

STEP 6. The Capital Credit Insurer insures each of the COA loans.

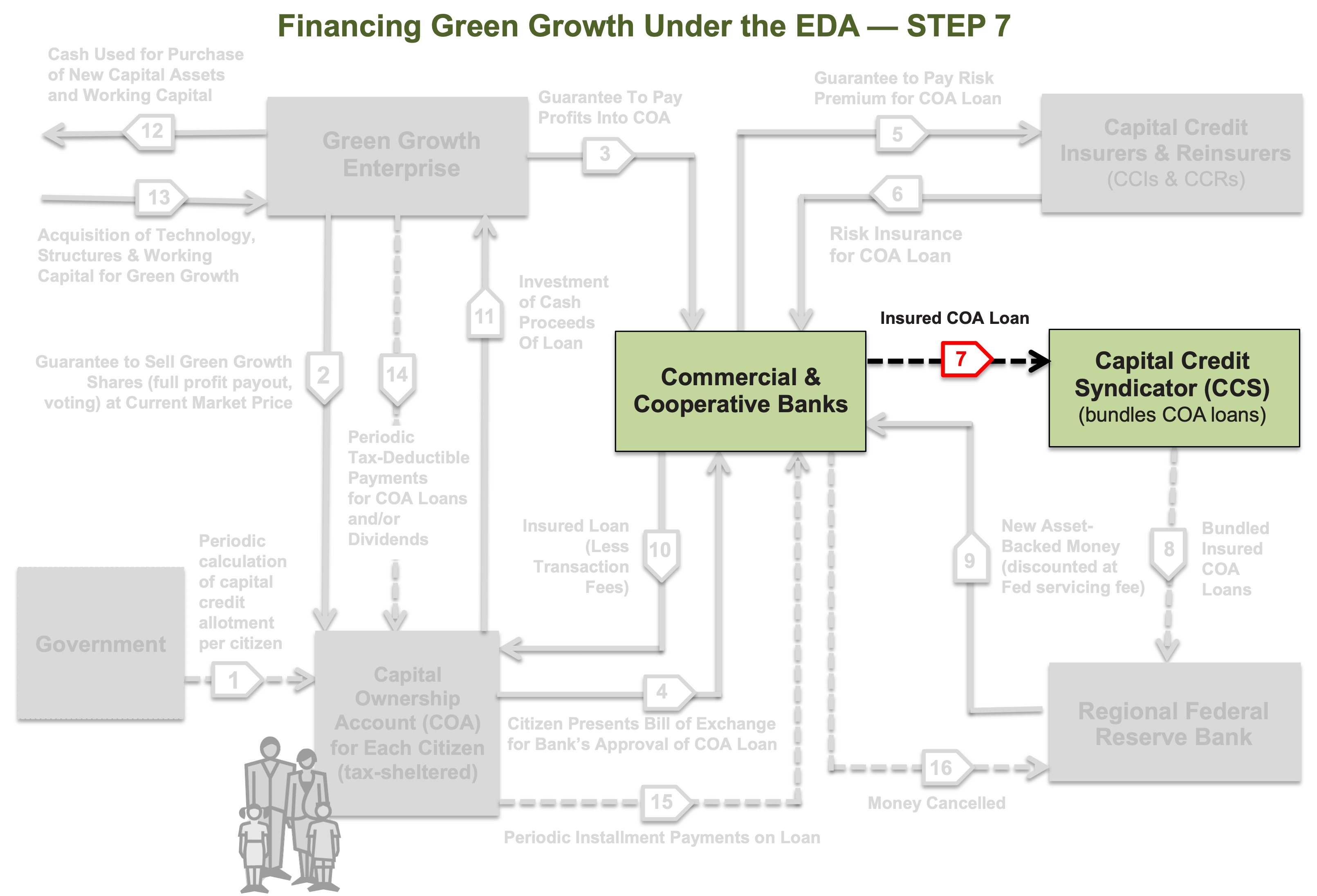

STEP 7. The local bank bundles (or transfers to a Capital Credit Syndicator) all its insured COA loans.

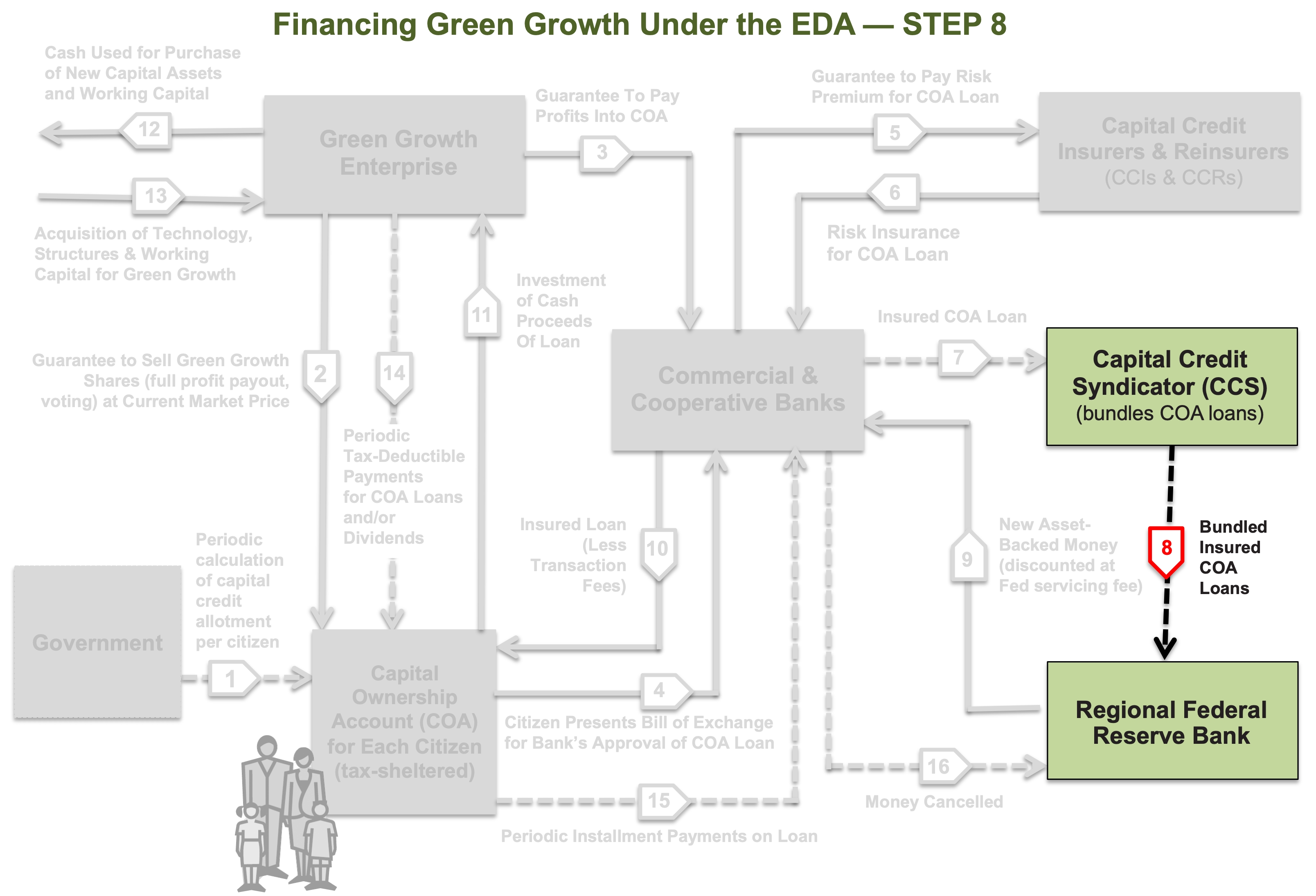

STEP 8. Either directly or through the Capital Credit Syndicator, the bank takes to the discount window of its regional Federal Reserve Bank the bundled COA loans for “rediscounting.” (This is where the Fed deducts from the total loan an amount to cover its own actual servicing costs for issuing new money.)

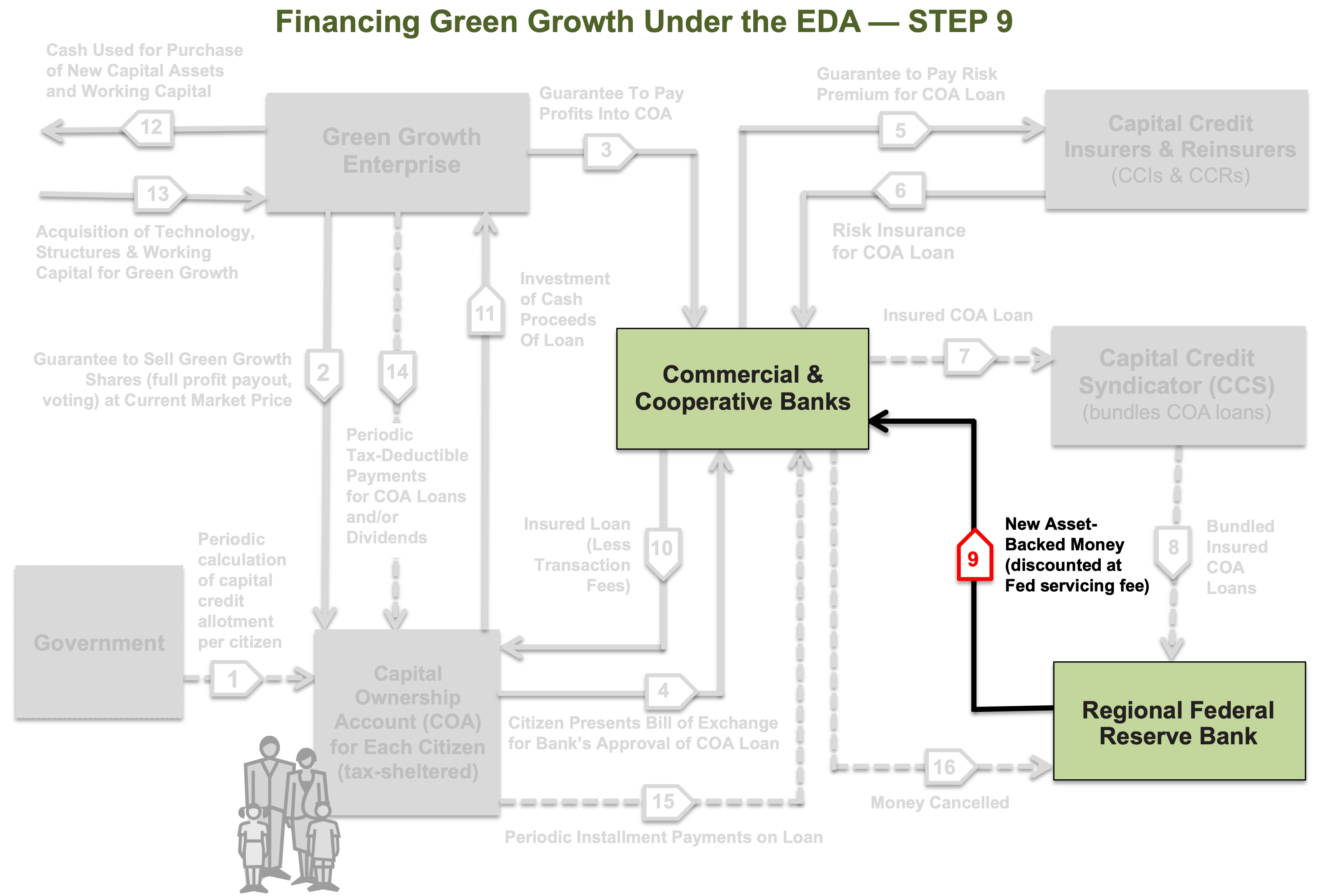

STEP 9. The regional Fed issues to the local bank a promissory note and creates new asset-backed money or “demand deposits” (a checking account) for the local bank.

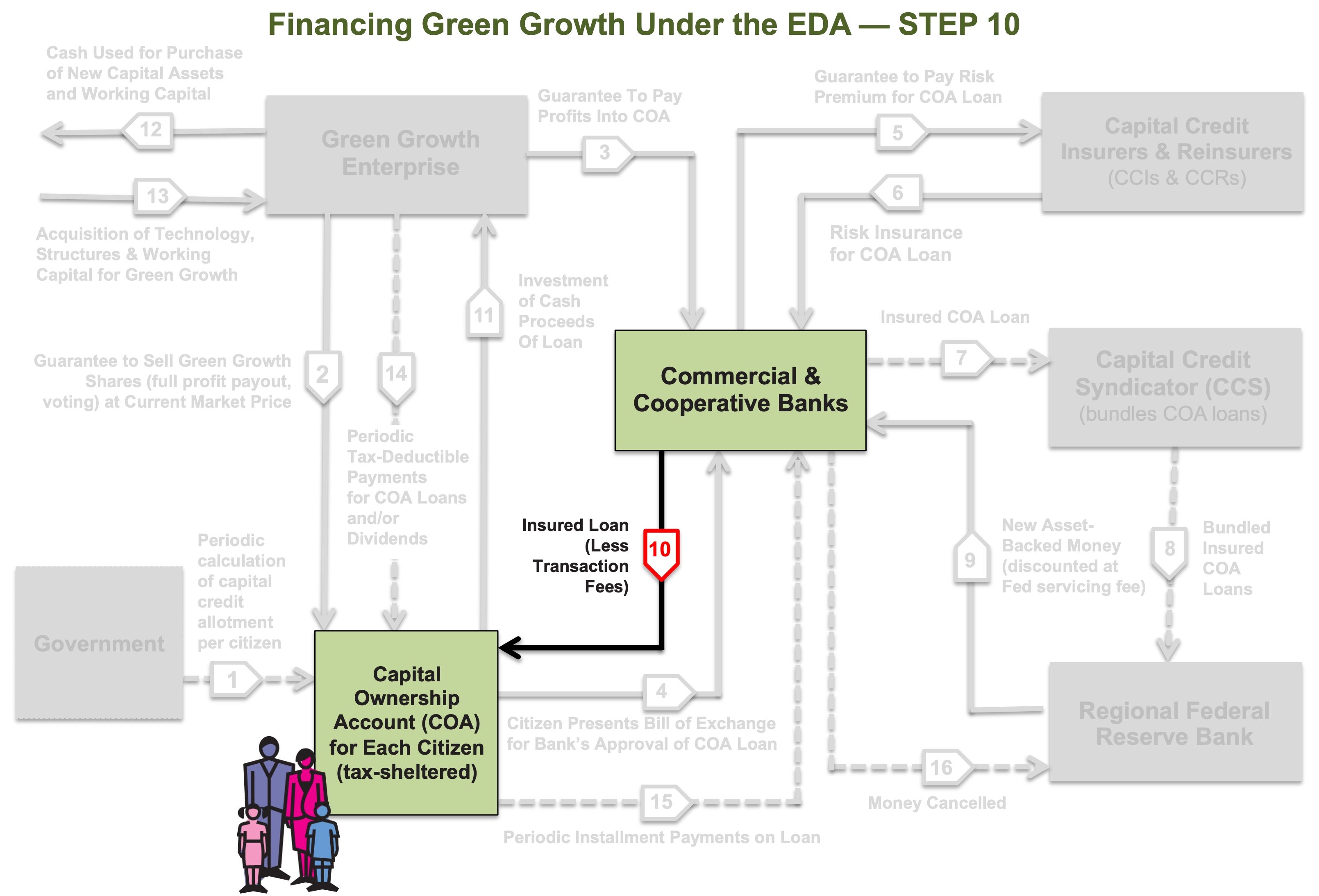

STEP 10. The local bank then transfers to the citizen’s Capital Ownership Account the new money to be used to purchase the newly issued shares of the enterprise.

STEP 11. The citizen writes out a check from his or her Capital Ownership Account to purchase the new growth shares.

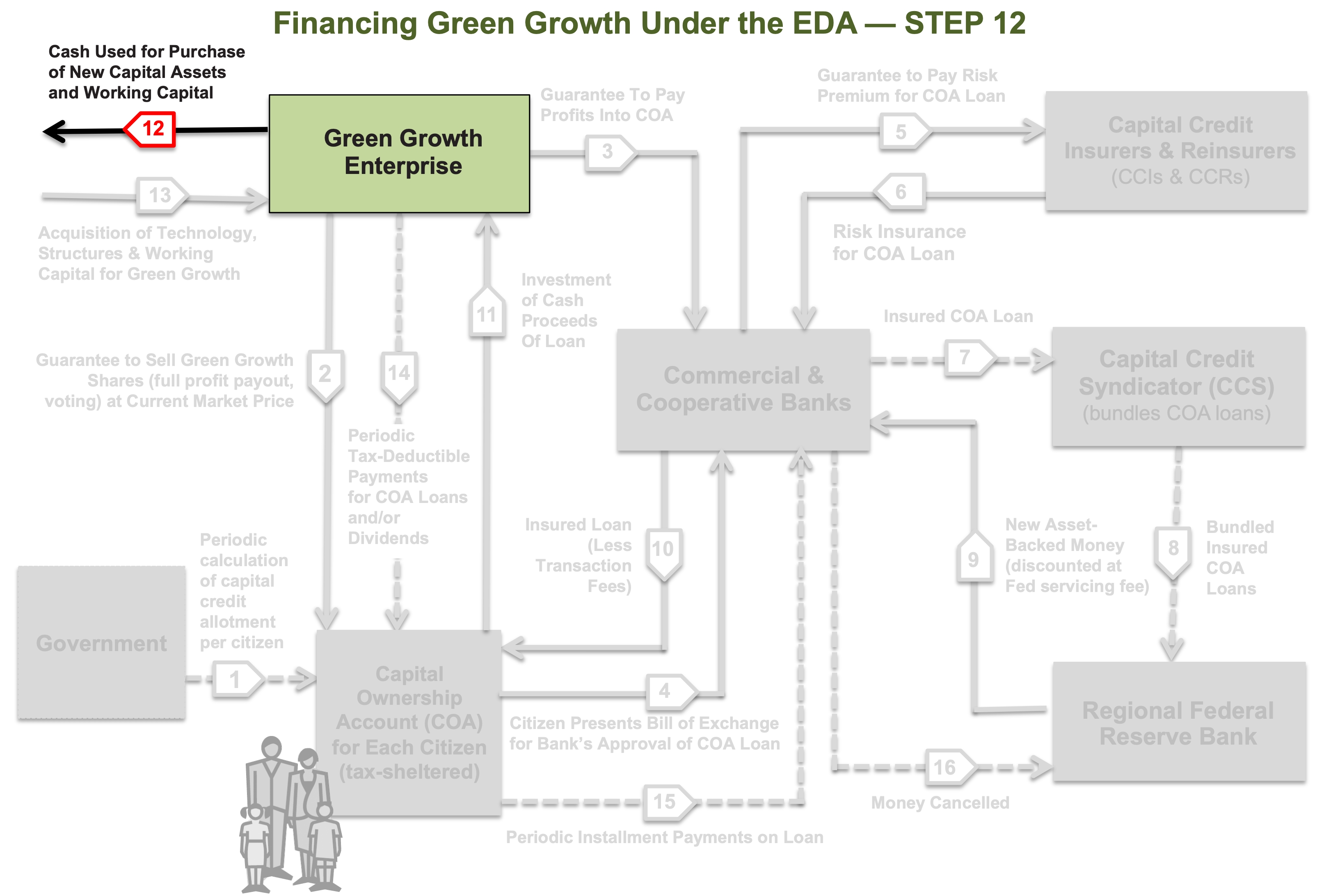

STEP 12. The enterprise uses the cash to purchase new capital assets and working capital.

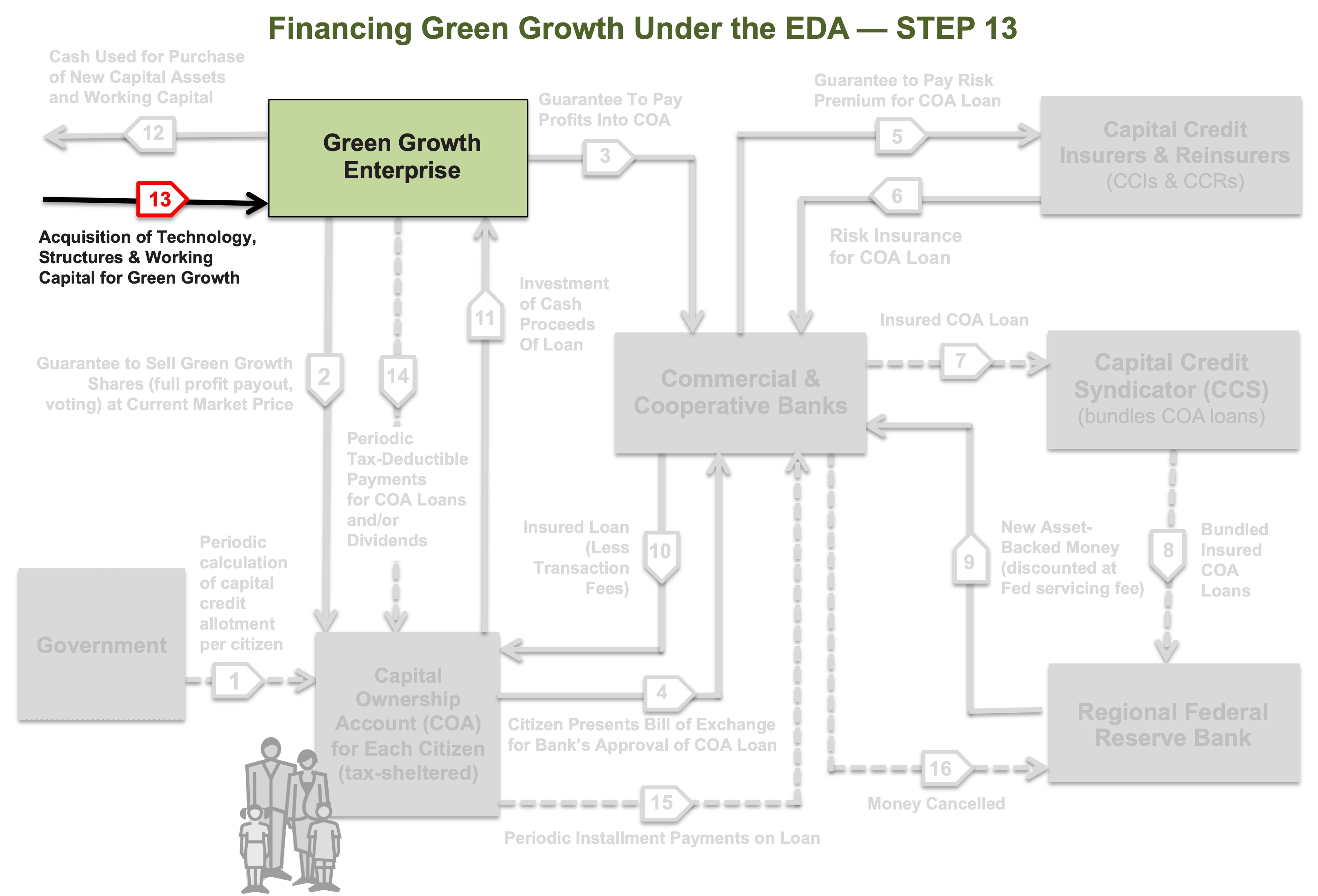

STEP 13. The enterprise acquires and puts into operation the new capital (technology, structures, land, etc.) to increase its production of marketable goods and services.

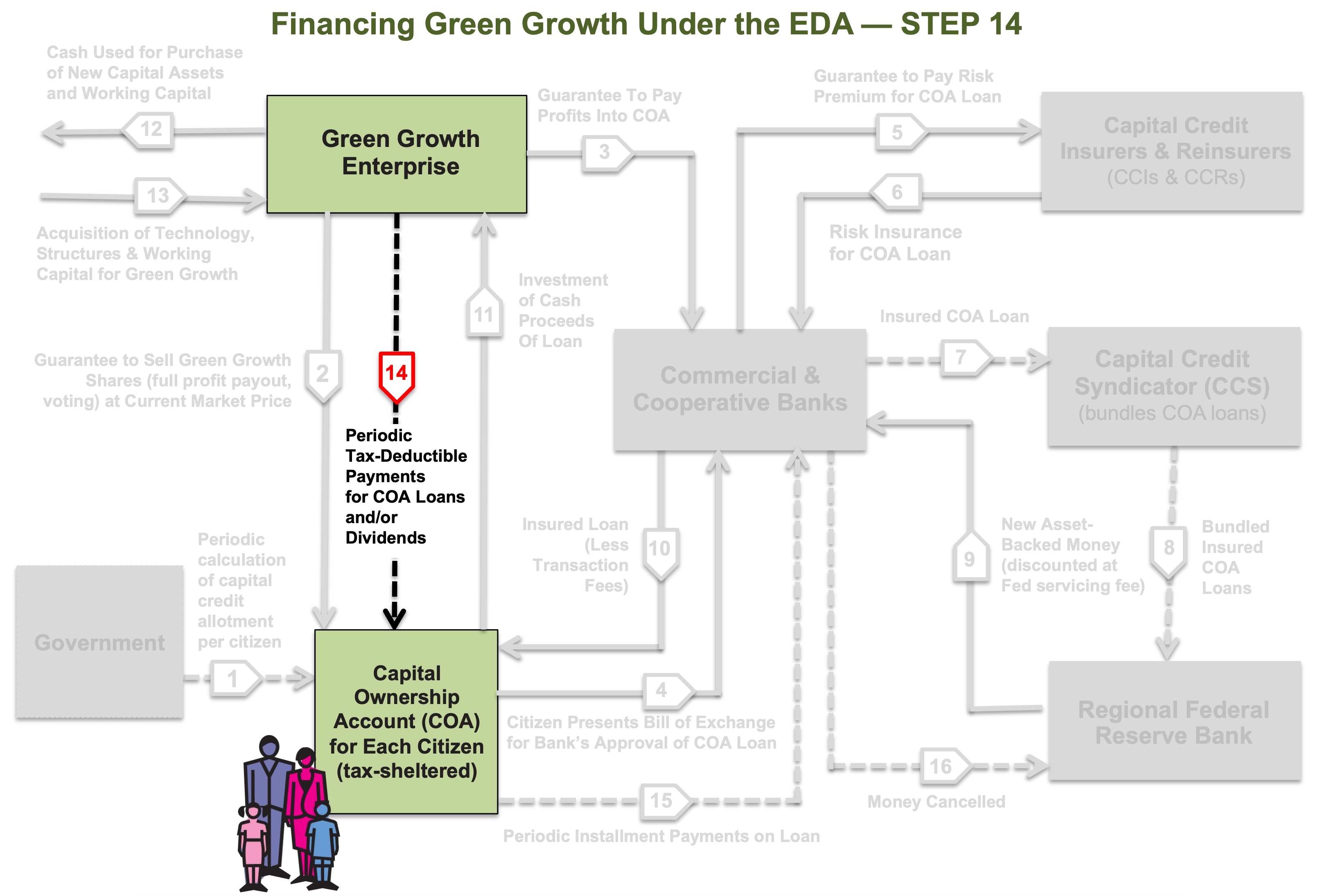

STEP 14. As it generates profits, the enterprise makes scheduled payments of dividends to the citizen’s Capital Ownership Account. These dividends are tax-deductible to the enterprise.

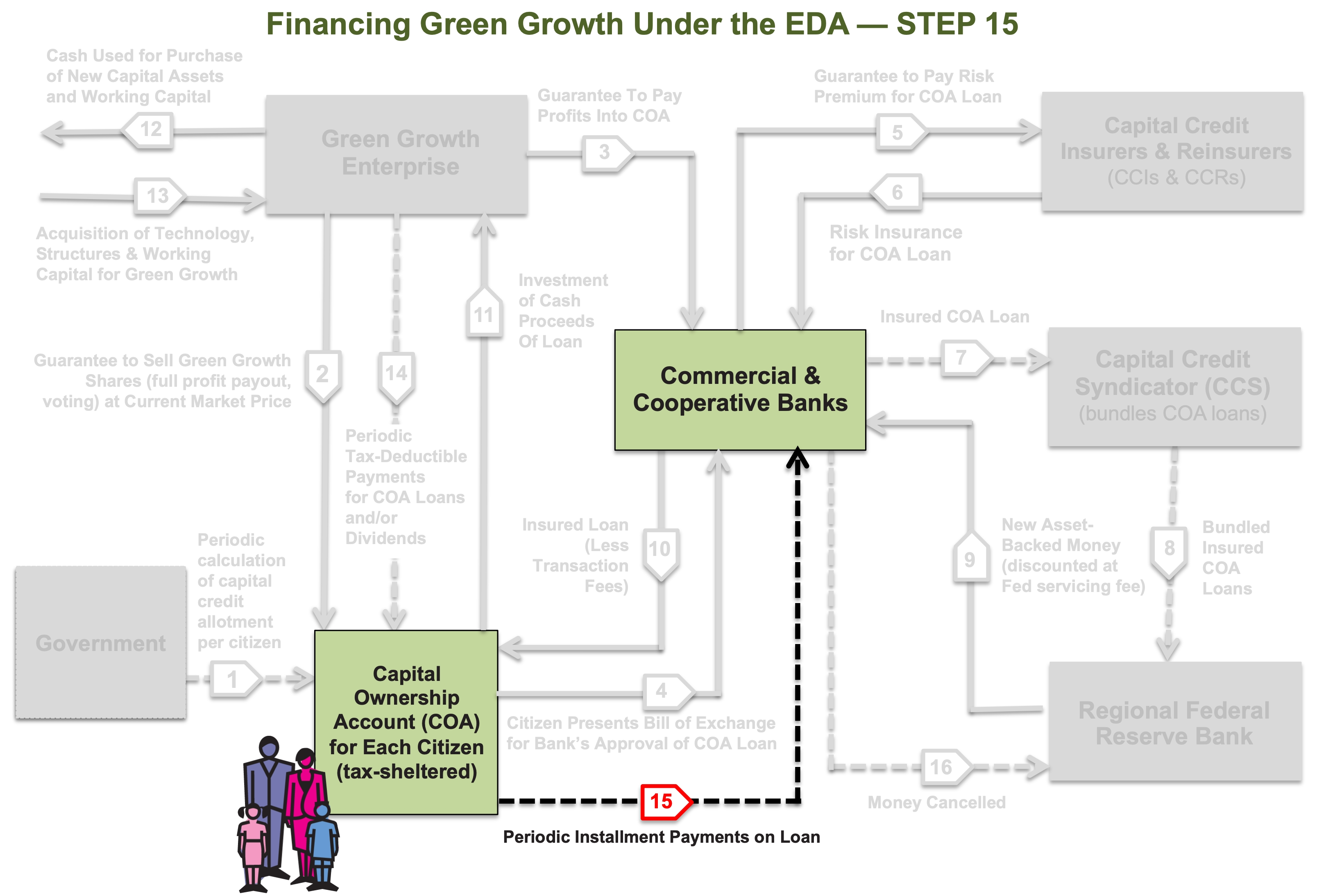

STEP 15. The Capital Ownership Account makes periodic installment payments of principal on the citizen’s COA loan. Once principal payments on that loan are fully paid, all additional future dividends become a new source of consumption income for the citizen.

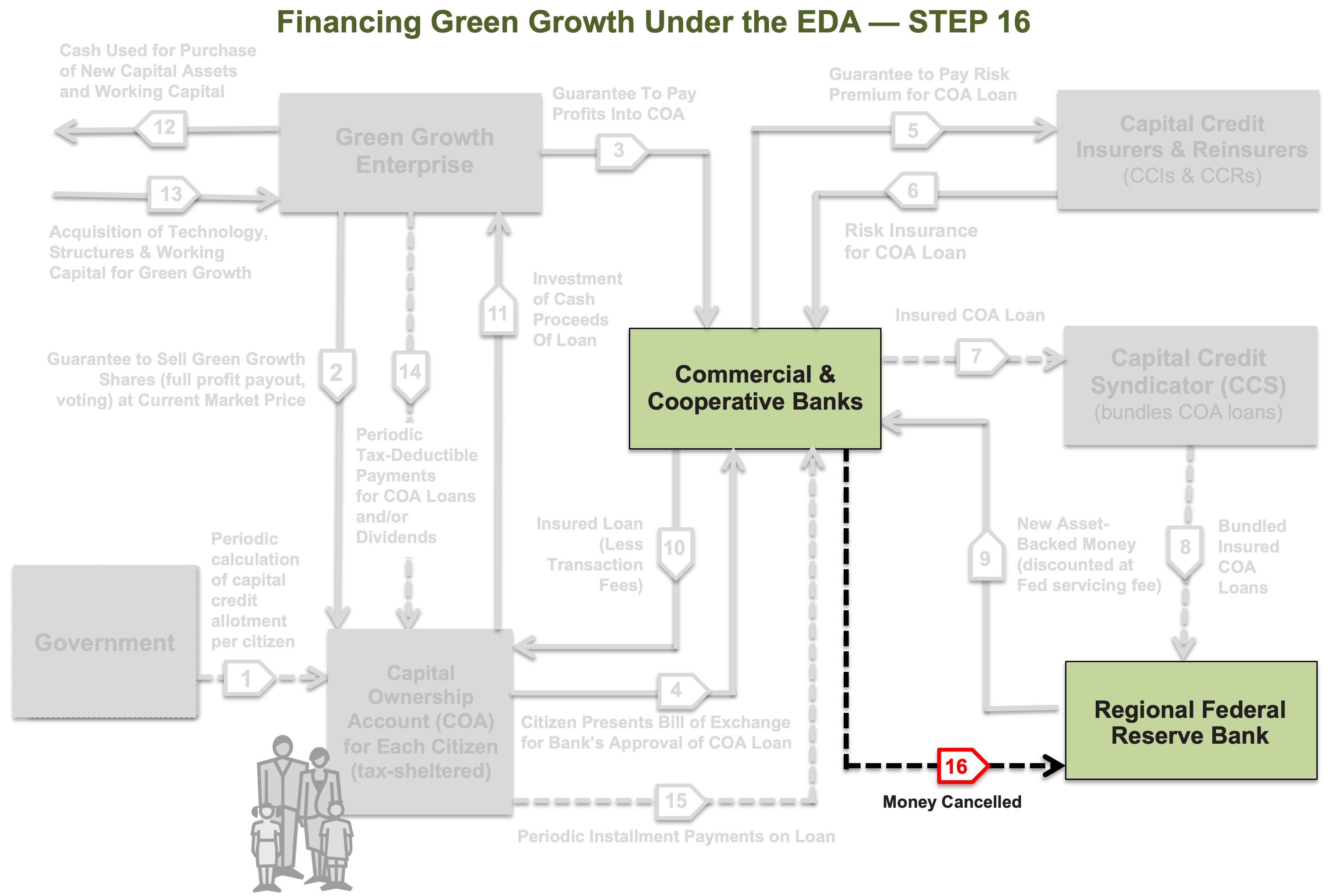

STEP 16. The money creation cycle within the Economic Democracy process ends with the original money being cancelled. This prevents the inflationary effects of money remaining in the economy that is not backed by capital assets or marketable goods and services.