by Norman G. Kurland and Dawn K. Brohawn

Paper presented to American Banker Conferences on ESOPs, New York City, June 12-13, 1989, as revised by authors, 1993

Introduction

“Privatization” has become a buzzword with many meanings. It can mean anything from restructuring basic economic institutions to foster a competitive free enterprise system (i.e. policy reform), to various methodologies for encouraging the private sector to perform services now being provided within the public sector. These methods can range from the elimination of subsidies and the lowering of trade barriers, to the shutting down of highly inefficient public-sector enterprises; from the sale of assets or shares in state-owned enterprises to private investors, to the contracting out of services now being performed by public-sector entities.

Regardless of how we define privatization, the predominant method today is to seek out existing savers, either domestic or foreign, who can purchase state-owned enterprises. Considering that most people live from hand-to-mouth and have very little savings to invest, particularly in high-risk, heavily subsidized state-owned enterprises, the concept of depending on existing savings pools automatically relegates most of the future ownership of these divested enterprises to only those with sufficient savings, i.e. those who already own and control most of today’s private sector enterprises.

Furthermore, the very people who most need to be motivated to make these divested enterprises operate profitably-the employees-are viewed as outside contractors. In general, participation by workers, labor unions and citizens generally in the restructuring process and in the intended benefits, is at best an afterthought. Consequently, in many countries where privatization has been launched, there is often tremendous resistance from unions, workers and consumer groups who have learned that privatization may mean that they have to give up something, with little or nothing in exchange.

In response to this resistance to privatization, there has been a groundswell of interest in enabling employees of state-owned enterprises to own a piece of the action. However, these efforts have tended to be both superficial and limited. As advocated by the world’s leading investment bankers who have become interested in privatization, “employee ownership” automatically means a 5-15% share for the employees. This “accepted” percentage of employee ownership is usually calculated by the “privatization gurus” based on what they think the employees of these enterprises can afford.

Thus, employee ownership (or broadened ownership generally) in the privatization process has often been promoted by specialists in one of two ways: 1) where the workers are thrown a few ownership crumbs to reduce their political resistance to privatization or to drive a wedge between workers and their labor unions; or 2) through public offerings where the majority of ownership and control will flow to wealthy domestic and foreign investors. We would lump together all these methods as part of the zero-sum approach to privatization, where the past controls the future and where one can gain only at someone else’s loss.

The momentum for privatization is part of the pendulum swing away from socialism-which has proven to be unworkable-to something new. This “something new”, however, cannot merely be a return to private sector “wage system” solutions with little or no safeguards against exploitation of workers and special privileges for the few. It cannot ask the workers to make concessions and sacrifices, and to work more efficiently, but for someone else’s profits.

Privatization in the traditional way, for different reasons than with socialism, also won’t work. The greatest obstacle to privatization is that privatization experts have been locked into the “past savings” paradigm.

An alternative paradigm that would make privatization practical involves synergy-creating new capital ownership opportunities for nonowners, without taking away existing wealth from present owners. And in most cases, this means maximizing participatory ownership opportunities for workers and citizens generally. Traditional approaches to privatization, because they are based on zero-sum game concepts and depend on previous savings and wealth, make it impossible to maximize ownership opportunities for ordinary workers.

Furthermore, ownership opportunities mean more than just the acquisition of shares. They also provide for the full empowerment of workers as first-class shareholders of the companies for which they work. Recent studies by the National Center for Employee Ownership (Oakland, California) offer evidence of a correlation between improved corporate performance and corporate cultures which integrate gain-sharing and participatory management with a democratically structured ESOP.

It has become a cliché among privatization professionals that “privatization is primarily a political process.” This is certainly true, but the problem is in the paradigm of political economy from which they approach privatization.

To many policymakers, intellectuals, labor leaders, and workers in developing countries, the word “privatization” suggests “monopolistic capitalism” and a return to colonialism. In view of the top-down approaches to privatization that have been fostered by privatization experts and investment bankers around the world, the critics of capitalism are right: workers are unlikely to gain more than token benefits if others own and control their jobs. A new approach is needed, one that transcends traditional socialism and traditional capitalism.

Perhaps the time has come for advocates of economic justice within a free enterprise framework to abandon the word “privatization” in favor of the term “democratization” (a word which has admittedly been misused and abused by those opposed to free enterprise and private property). Words like “democracy” and “justice” are good words, however, and should not be abandoned to be monopolized by the left.

Expanded Ownership as a New Pillar of Economic Policy

Both public and private lending institutions have been prime culprits in fostering state ownership of productive enterprises. In the light of the world debt crisis, however, these financial institutions are beginning to face up to the errors of the past. As the primary U.S. federal agency charged with assisting developing countries in their economic growth strategies, the Agency for International Development is seriously examining the expanded ownership model. In its policy paper on “Private Enterprise Development” (March 1985, page 15), USAID states: “AID encourages the introduction of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) as a method of transferring a parastatal to private ownership.”

In a cover letter sent on May 6, 1988 which distributed the book Every Worker an Owner (Center for Economic and Social Justice, Arlington, Virginia) to all USAID mission directors around the world, Administrator Alan Woods stated: “I’m convinced that whatever we do to expand the number of people who have a stake in LDC economies will help to bring about sounder policies.”

In 1988, two Presidential commissions have reaffirmed these principles. The Presidential Task Force on Project Economic Justice defined expanded ownership as “a new cornerstone for the future of U.S. economic policy.”

President Reagan’s Commission on Privatization, which issued its final report in April 1988, recommended that “employee stock ownership programs should be promoted by the Agency for International Development as a method of transferring state-owned enterprises to the private sector in developing countries.”

And in January 1988, the Debt Management and Financial Advisory Services Department of the World Bank released a document entitled “Market Based Menu Approach” which included the following:

Debt conversions in employee stock ownership plans are a special case of debt-equity transaction. A U.S. presidential task force, headed by former Ambassador William Middendorf, proposed to encourage debt-equity swaps to privatize parastatal enterprises through the conversion of U.S. bank loans to equity, and then selling the equity to workers by means of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs)…

A Case Study: The Alexandria Tire Company Employee Stock Ownership Plan

The Alexandria Tire Company (ATC) project in Egypt, supported jointly by the Egyptian government and the USAID mission in Cairo, represents the first practical application in the developing world of the expanded ownership paradigm and the power of productive credit as a catalyst for economic democratization. ATC was launched as a joint effort of the Minister of International Cooperation of the Arab Republic of Egypt and the Cairo Mission of the United States Agency for International Development.

General

The project consists of the construction and operation of an all-steel radial truck tire manufacturing plant at a site at the Ameriya Industrial Complex near Alexandria, Egypt. The project, which will create 750 new private sector jobs, will be implemented under Egypt’s Investment Law (officially titled “Law No. 43 of 1974, Investment of Arab and Foreign Funds and the Free Zones, as amended by Law No. 32 of 1977”).

Project costs, estimated at 370 million Egyptian Pounds (or over $160 million), will create a facility capable of producing 350,000 heavy-duty truck and bus tires annually for the domestic Egyptian market, roughly 30% of the total market demand. At present, some 70% is imported (the state-owned manufacturer TRENCO produces 280,000 units) and consumption is about 1 million a year. In addition to tire production, the project will include the manufacturing of carbon black, at an annual capacity of over 15,000 tons. By cutting foreign imports of this key ingredient, the project will generate additional annual savings in Egypt’s balance of payments.

Of the project’s total capitalization, 56% will be debt financing and 44% will be equity financing.

A new independent corporation will be formed, the Alexandria Tire Company (ATC), whose 56% debt financing (£E 207 million), will come from three hard currency sources:

The Italian government has allocated a loan of $59 million (£E 136 million), half of which is at an interest rate of 1.5%. The repayment period will be 20 years, including a 10-year grace period.

Foreign supplier credit will be $10 million (£E 23 million).

The European Investment Bank will provide $27 million (£E 48 million) in European Currency Units, at 2% lower than prevailing interest rates. The repayment period will be 12 years, including a 4-year grace period.

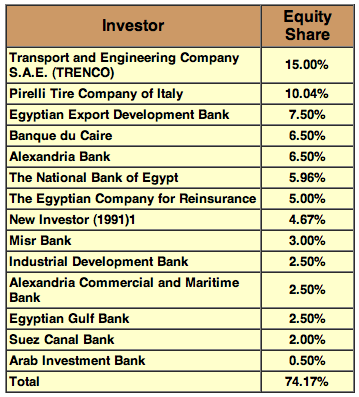

ATC’s founding equity investors (contributing 44% or £E 163 million of total project costs) will include:

In addition, a Worker-Shareholders’ Union (WSU)2 is being formed, with an Employee Share Ownership Plan (ESOP) as its bylaws, to acquire 25.83%,3 or 421,000 of the founding common shares of the new venture, 252,600 shares to be divided among the 750 newly-hired employees and 168,400 shares among the 3,500 employees of TRENCO, the “mother company” of the new venture.

The new venture will transfer to Egypt three kinds of “state-of-the-art” technology:

World-class steel-belt radial tire technology backed by technical support by one of the world’s leading multinational corporations;

The Employee Share Ownership Plan (ESOP) to be administered by a Worker-Shareholders’ Union, an advance in ESOP corporate finance technology;

A new reservoir of low-cost capital credit for promoting worker ownership.

The ESOP

The ESOP uses self-liquidating productive credit to enable workers to become shareholders without reducing their savings or paychecks. Besides implementing the first ESOP in the Third World, the project will also launch the world’s first Worker-Shareholders’ Union (WSU) as a legal vehicle for implementing the ESOP, guaranteeing worker ownership participation and democratizing management accountability. The WSU, originally called an “Employee Shareholders’ Association” (ESA) was invented to substitute for a legal trust, the mechanism which is used to implement ESOPs in the United States and the United Kingdom, but which does not exist under Egyptian law.

To finance the acquisition of the 25.83% of founding common shares by employees, the Egyptian Government through its Ministry of International Cooperation (MIC) has approved a loan of £E 42.1 million ($16.5 million) from funds generated by the sale of U.S. commodities under the USAID Commodity Import Program and deposited into an account termed the Special Account. Until the WSU is formed the loan will be made to the National Investment Bank of Egypt (NIB), as temporary borrower and fiduciary for the purchase of shares for the employees, and, after the first 200 employees are hired and the WSU is established, the loan from MIC will be assumed by the WSU along with legal title to these shares.

During the 3-year construction phase and another 3 years needed by the company to become fully operational, there would be a grace period for repaying the ESOP loan. The loan, on Islamic banking terms as explained below, would be repaid over the following 10 years wholly out of projected dividends. No employee payroll deductions would be required. During the 16-year loan period, the workers’ shares would be pledged as the sole source of security on the loan. As the loan is repaid over years 7-16, the personal accounts of all participating employees would reflect shares which have been paid for during the current year and allocated among all employees according to the formula contained in the WSU. Terminated employees would have their shares cashed out by the WSU or the company.

Impact on Employees

How will the ESOP affect the average ATC employee? The average Egyptian tire manufacturing employee presently earns about £E 4,000 (about $1,600) annually. Assuming wage levels remain the same at the Alexandria Tire Company and share values do not increase from their original acquisition price, the average ATC worker (according to the feasibility study for the project) will accumulate through the ESOP over £E 33,000 worth of shares, more than 8 times his annual wages; in addition, by the eighth year after operations begin, the average ATC worker will receive a second income from dividends of £E 3,300, over and above the dividends used to repay the ESOP debt or set aside for repurchasing his share rights upon retirement. After the ESOP loan is repaid, the average worker’s capital income will amount to about £E 11,800 per year. And through the voting of his shares in the ATC Worker-Shareholders’ Union, he will have a voice in selecting 30% of the ATC board members and in other matters subject to shareholder voting.

TRENCO

ATC is the child of TRENCO, which was founded in 1946 as a general engineering company. In 1956, TRENCO began the manufacturing of tires and is today the only tire manufacturing facility in Egypt. While this 3,500 employee company is 100% owned by the Government of Egypt, TRENCO is one of the few profitable state-owned enterprises, a tribute to its superior management team. It currently produces 1.1 million tires per year, of which 280,000 are truck tires. In 1984, TRENCO entered into a licensing agreement with Dunlop Tires to produce automotive radial tires. It is now producing 150,000 automotive radials a year, but none are steel-belted radials. TRENCO will provide the plant site, the engineering and other technical inputs to construct the facilities and infrastructure, and approximately 26,500 tons of raw materials per year.

Pirelli Tire

Pirelli will supply the steel-belt radial technology needed by ATC. Pirelli was founded in 1923 and has a worldwide network of tire producing and distributing facilities, either wholly-owned or in joint ventures. The company produces tires for all automotive markets and possesses patents on special manufacturing technology for several tire production processes. The steel-belted truck tire production process for the type and size needed by Egypt is one such patent. Pirelli has entered into 37 joint ventures and has granted 51 licenses to manufacture its products. Thus, Pirelli has a proven track record of productivity and worldwide operational experience. Pirelli will provide all machines, moulding equipment, moulds and engineering to plan and install the equipment. Under a 10-year technical assistance agreement, Pirelli will train engineers and technicians and assist in the production process.

Financial Feasibility

Egypt’s current demand for truck and bus tires is 1.0 million per year. From 1975 to 1985, demand grew by 20% per year and is projected to grow at approximately 8% during the decade 1985 to 1995. Approximately 40% of the demand is supplied by domestic production. TRENCO is the only domestic producer, but does not produce steel-belted radial truck tires.

Expected Outcomes

The project is expected to begin production of tires by the end of project year three.4 By the end of project year five, ATC is expected to reach design capacity, 350,000 truck and bus tires per year. During this time, 750 new jobs with a payroll of £E 4 million will have been created in the private sector. ATC is projected to capture over 30% of the current and future domestic truck and bus tire market, producing net earnings of £E 31.1 million on net sales of £E 198.6 million by the year 1994. Overall internal rate of return for the project, from inception to 2006, is expected to be 17.7%.

Other macroeconomic effects of the project will include:

Foreign exchange savings resulting from domestic tire production of $20-25 million annually, plus an additional savings of $10 million annually from domestic production of carbon black;

Loss of Egyptian customs revenue on imported tires averaging $20 million annually, which would be largely offset by £E 30 million annually in corporate taxes by the year 2003, plus dividend and salary taxes;

Dividends of £E 30 million annually, 90% to Egyptians, within 6 years from start-up;

A model of a “new labor deal” for Egyptian workers, which would be structured to restrain inflationary increases in fixed labor costs while enabling workers to increase their incomes significantly from productivity gains and profits;

Structural reforms to encourage innovative corporate strategies which would provide Egypt with long-term competitive advantages in the global marketplace.

Special Credit Incentives for Leveraged ESOPs

Normally, in its worldwide private sector development strategies, USAID requires the use of an unsubsidized, market-related interest rate and a reasonable degree of assurance that the loan pool can be restored by loan repayments and made available for future private sector loans. The ATC ESOP project represents a breakthrough, both in its insistence on the democratization of access to productive credit and in its innovative use of Islamic banking practices for reducing the cost of such credit to workers and for increasing the likelihood of restoring the principal to the loan pool for future ESOP loans.

A major constraint that USAID has had to face in setting its interest rate policy is Egypt’s inflation, which runs at an estimated annual rate of 20%-25% or higher and shows no signs of slowing down. An AID economist ran several scenarios to calculate the inflation-adjusted purchasing power of repayments of the £E 42.1 million ATC ESOP loan with different interest and inflation rates. These scenarios demonstrated that an interest rate of 7%-13% would recover only about 1/4 to 1/2 of the purchasing power of the loan.

Equity Expansion International’s Egyptian legal advisor to this project, Mahmoud Fahmy, advised USAID that according to the Egyptian civil code (Article 227) a non-banking entity, such as MIC, is legally prohibited from charging an interest rate which exceeds 7%. With an interest rate of 7% and a 20%-25% inflation rate, only 23%-33% of the purchasing power of the loan would be recovered. On the other hand, Counsellor Fahmy stated that if ATC’s obligation to repay MIC is stated as an absolute obligation to return the inflation-adjusted loan capital, without expressing it as a profit- and risk-sharing arrangement, such an arrangement would not be legal under Egyptian law since the inflation adjustment would be legally regarded as “disguised interest.”

To avoid the conflict between Egyptian law and USAID’s policy objectives of promoting unsubsidized interest rates and preserving the purchasing power of the ESOP loans, AID and the Egyptian government adopted an innovative credit policy based on the Islamic concept of “profit-sharing and risk-sharing”. Under the proposed profit-sharing approach, in lieu of interest and principal payments, MIC will receive 50% of the ESOP dividends, which amount to 15.25% of ATC’s total distributed profits over a 10-year period following the construction and start-up phase (project years 7-16). Based on the feasibility study performed by Pirelli and TRENCO, a 50% MIC participation in the ESOP’s share of dividends for that 10-year period is projected to recover 116% of the purchasing power of the loan (the extra 16% being regarded as MIC’s administrative fees and risk premium). It is expected that MIC’s profits would also increase along with rising price levels and inflation-adjusted prices of truck tires, thus protecting the lender’s capital.

The profit-sharing arrangement is conceptually compatible with the idea of employee ownership. The employees will be able to acquire ownership and pay back the loan only if the company is profitable. Thus, employee ownership as well as full recovery of the loan will depend on the performance of the employees and of the company. If there are no profits, the employees get nothing, owe nothing, and the shares reserved for them would be sold to the private sector at large. Since the employees have no attachable assets, in the absence of corporate profits it would be a practical impossibility to turn to the employees for repayment of the loan. And, like the borrower, the lender (for a predetermined period) is linked directly to the productivity and profits of the company. The profit-sharing formula thus appears to be an ideal solution which satisfies the concerns of USAID, MIC as the lender, ATC investors and management, the union likely to represent ATC workers, and the future employees.

USAID approved this new self-liquidating credit arrangement on April 4, 1989.

Reaction in Egypt to the ESOP innovations at the Alexandria Tire Company appears to be highly favorable, and even enthusiastic. As a result of the ATC model, the Egyptian Higher Policies Committee and the Committee for Economic Affairs has approved an additional £E200 million of funding from USAID’s Special Account to initiate the stock sales of qualified government enterprises to their employees through ESOP financing. Already about a dozen government-owned companies are under consideration for these ESOP buyout loans.

The Egyptian press has also reacted favorably to the ATC model. A slew of articles have appeared, including a full-page piece on ESOP in the leading Egyptian paper Al Ahram (March 23, 1989, p. 9), and a 5-part series on ESOP by American University of Cairo’s Professor of Management Dr. Khaled Sherif in the prestigious Al Ahram Economist weekly.

An article in Al-Gomhouria entitled “Word of Love” (Jan. 23, 1989) comments:

USAID offered a present to the workers of Egypt. They offered £E 80 million…to be kept at a Special Account where workers will be able to attain loans that would enable them to buy shares in their plants . . . Repayments will go back into the Account to provide additional loans to other workers and not to be returned to the U.S.

. . . The idea is new for us, but will convert the workers into owners and not employees of the new plant-shareholders, not bystanders. The worker’s heart and soul will be directed to the success of the project. The feeling is that the worker, because of the ownership in the project, will be more loyal to the company and its success. In addition, the worker will receive incentives and dividends from the shares he owns.

Conclusion

Some advocates of privatization believe that who owns and enjoys the rights and powers that flow from private property is unimportant. This attitude, in our opinion, ignores the relationship between property and the empowerment of those who own and control modern instruments of production. It reflects the “fatal omission” in traditional approaches to economic development which has engendered the politics of nationalization in the first place. And it leads inevitably to concentrated control over production and basic economic decisions, and to the very opposite of effective economic policy for a democratic society.

We would argue that sharing ownership and control of modern productive property is a matter of justice and a fundamental human right, and that the democratization of private-sector capital ownership should be a basic pillar for the future of any nation’s economy.

If greater efficiency is the goal of privatization, the question should be raised: Can a society have economic efficiency without economic justice? Without justice there can be no harmony in the workplace or in the economy. And social and economic justice is impossible without a system of decentralized participation, accountability and economic power. Since power and accountability follow control over productive property, and the ownership of productive enterprises is largely determined by who has access to capital credit, the key to genuine democratization of society lies in decentralized access to future productive credit among workers and consumers, as directly and personally as possible.

Good practice follows sound ideas, and successful privatizations will involve a delicate balancing of principles of efficiency with maximizing ownership opportunities for today’s disenfranchised workers and citizens. This process will necessarily evolve gradually, as policymakers, corporate executives, labor leaders, and institutional lenders lift their minds above the zero-sum paradigm to a more synergistic framework designed to make every citizen an owner.

Notes:

1 – In 1991 additional equity investment was added in the amount of £E 24, 982,000, providing an additional 4.67% share of equity participation.

2 – The law authorizing the formation of a Worker-Shareholders’ Union (WSU) was approved by the Egyptian National Assembly on June 22, 1992 as Chapter VIII of the Capital Markets Law (Law No. 95 of 1992. When ATC was first formed this entity was called an “Employee Shareholders’ Association.” After approval from the Capital Market Authority of Egypt, this entity will receive shares acquired on behalf of the ATC workers by the National Investment Bank of Egypt.

3 – The original equity acquired for workers gave them a 30.5% share which was reduced to a 25.83% share when new equity was raised, as described in note 1. This dilution resulted from the fact that the loan available to workers could not be increased beyond the original £E 42.1 million.

4 – According to Fathy El-Feky, Chairman of ATC, building construction began in June 1992 and completion is expected by November 1993. Actual full-time operation is expected to begin in June 1994.