by Rodney Shakespeare

August 2000*

Is there a Third Way? No, not if by ‘Third Way’ is meant the vacuous rhetoric of Clinton and Blair which likes to give an impression of progressive policy while keeping the reality to the right of centre.

A few years ago, the British Labour party and the American Democrats could have been expected to be social democrats (i.e., supporting a mixed economy with relatively high levels of state spending). Today they are simply proponents of ‘free market’ capitalism. Elsewhere in Western Europe, the picture is largely the same despite some traditional socialist rhetoric coming from France, for example. Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.

Nor, at present, is there any prospect of future change. This is because there is no new paradigm from which fundamental new policy can arise.

A paradigm is a basic framework for understanding reality. An example is the conventional linear paradigm for understanding economic and political issues. This paradigm places some idealised form of communism on the left end of a horizontal line and some idealised form of laissez-faire capitalism on the right. In between are all the other economic and political forms. Thus the linear paradigm conceives of all existing economies and political forms as either left, or right, or a centrist mix of left and right – for example, forms of ‘social democracy’. Similarly, all theories, critiques and proposals are left, right or a centrist mix.

The conventional linear paradigm.

The linear paradigm, moreover, does not, and cannot, conceive of anything lying outside or beyond that line. The line therefore encompasses all ideas or policies – left, centre, or right – and, in some way, all are connected.

Yet surely, it might be said, communism and ‘free market’ capitalism cannot be connected: they are opposites. Are they? Consider productive capital. Under communism, perhaps 5 – 10% of the population, constituting the nomenklatura, control the productive capital while, under ‘free market’ capitalism, perhaps 5 – 10% of the population own the productive capital.

The 5 – 10% controlling or owning are hardly opposites: they are largely the same with much privilege, power and wealth in the hands of a small group. A real opposite would have every individual in the population substantially involved with the productive assets. Indeed, it is puzzling that nowhere on the linear paradigm is there a manifestation of 100% of the population privately and individually owning productive capital. Not only is there no manifestation on the line, but many people – and perhaps some people in this room – are constitutionally incapable of even conceiving that 100% ownership. Moreover, even if they can conceive it, they quickly start to object saying “It doesn’t matter who owns the capital” or “Jobs and welfare are perfectly adequate for most people: they don’t need to own capital.”

Yet binary economics most certainly conceives of that 100% individual ownership, an ownership continually paying out a very substantial income. Furthermore, it is an ownership independent of whether or not a person is in the labour market. To those who say that jobs and welfare are enough, binary economics replies that many people, such as carers, cannot labour; jobs are rarely secure; and jobs for most people do not pay sufficient so that there has to be massive redistribution in one way or another. To which can be added the humiliations and frustrations when having to obtain welfare benefit from the state.

The question now arises as to why the linear paradigm does not contain 100% private and individual ownership? Why is it constitutionally incapable of conceiving such a thing?

Well, the reason, of course, has to do with privilege, power and wealth. The 5 – 10% of the left and the 5 – 10% of the right – supported, of course, by thousands of academics and theoreticians whose career structures depend on not rocking the boat – have succeeded in promulgating a paradigm which maintains privilege, power and wealth for a small group. At the heart of that paradigm (which, today, is essentially the neo-classical paradigm) is an assumption about who or what creates the wealth. The assumption can be traced back to Adam Smith who, writing before the industrial revolution had actually happened, attributed all wealth creation to humans rather than productive capital. His factory where all those pins were made was really a manufactory which had men using hand tools and specialised labour rather than extensive machinery. It is true that Smith had some understanding of what might happen in times to come after his death but, that said, it is still fair to say he attributes all wealth creation to labour.

And, quite remarkably, so have all economic thinkers and economic schools since. That is not to say that some of those schools do not talk of the productive powers of capital when they wish to justify a financial return to capital but, in a very fundamental way, they use a concept – the productivity concept – which sees all wealth creation in terms of labour productivity. Even the neo-classical concept of capital productivity is ultimately to be explained in terms of labour productivity.

The over-emphasis on the human contribution to wealth creation suits the left (which can then claim that the workers do all the work, etc.) and it suits the right (which can then claim that since the workers do most of the work, it does not matter who owns the capital). In this way, conventional economics is able to keep capital narrowly owned or, previously, narrowly controlled.

So, in the conventional linear paradigm, all left, right and centre-mixed economies or proposals do lie on that line. All of them are based on conventional productivity and so all are but different manifestations of the same homocentric notion which denies the independent productiveness of capital. Inevitably and crucially, all the manifestations deny that any other economics (and the politics based on it) is possible unless it lies somewhere on the line.

Indeed, no matter how the situation is viewed, all conventional economics schools and thinkers are connected. Thus in 1983, K. Cole, J. Cameron and C. Edwards published Why Economists Disagree: the Political Economy of Economics. This book contains a diagram showing the historical development of economic theory and it places all the main schools and thinkers in three broad categories – Subjective Preference Theory; Cost-Of-Production Theory; Abstract Labour Theory. In particular, the diagram shows that all the schools and thinkers are in direct descent from Adam Smith and are all based on some concept of productivity.

But binary economics is not on that diagram and nor is it anywhere on the linear paradigm. This is because the binary paradigm is fundamentally new. It offers a systematically new approach precisely because it is not left, nor right, nor some centrist mix. It does not fall anywhere on a line between left and right. Simply, in conventional terms, it defies classification.

In considering how different the binary approach is, please note that binary economics is not based on the concept of productivity but rather is based on the foundationally different concept of binary productiveness. There is not time today to discuss binary productiveness in detail. Suffice to say that it brings out the important part played by capital in productive processes and it ultimately, on market principles, founds a private property system designed to diffuse rather than concentrate capital ownership. The result is private and individual capital ownership by 100% of the population.

Among the beneficial consequences of that ownership are the following:

- a tremendous change in the economic position and status of women;

- the balancing of supply and demand;

- a change in attitudes towards conspicuous consumption;

- a green growth; and

- hope for the voluntary control of population levels.

To which can be added large-scale solutions to the burgeoning problems of governmental pension and welfare expenditure. Regarding pensions, there is a demographic time bomb being largely ignored by European countries. People used to die in their 60s. Now they die in their 80s or even their 90s as will be the case with many of the people in this room. The state cannot provide reasonable pensions for those people. However, binary economics, (over time, on market principles) ensures that there will be no need for state pensions because all individuals will have their own income coming from their capital estate.

Rather similarly, in a binary economy, the need for welfare benefit will be greatly diminished again because all individuals will have income from their own capital estate. That income will exist independently of whether or not the individuals are in the labour market.

To try and give a little more understanding of binary economics, look back to the diagram of the linear paradigm where you may have noticed something a little odd – it does not actually show ‘free market’ capitalism but instead uses the phrase ‘unfree market’. Yes, unfree. Indeed, binary economics uses the term ‘unfree market’ to describe the situation in Germany, France, UK, USA and similar economies.

There are many reasons for saying they are unfree but the main one is because they all undoubtedly prevent most people coming to individual ownership of large amounts of productive capital. In the USA the present level of new capital formation is about $4,000 per man, woman and child per year. That is a huge amount but, each year, it remains narrowly owned, and will always remain narrowly owned, because the unfree market ensures that narrow ownership.

Binary economics, of course, widens ownership to 100% of the population and, in order to understand how binary economics does that it is helpful to know a little about the ESOP. The ESOP (or Employee Share Ownership Plan) was created by Louis Kelso, the original binary economist. There are now well over 11,000 ESOP schemes in the USA although, alas, the ESOP has never been legislated to conform with what binary theory demands. However, if you understand the present ESOP then you are a long way down the road to understanding how binary economics enables everyone, over time (nothing happens overnight in binary economics) to come to individual ownership of productive capital.

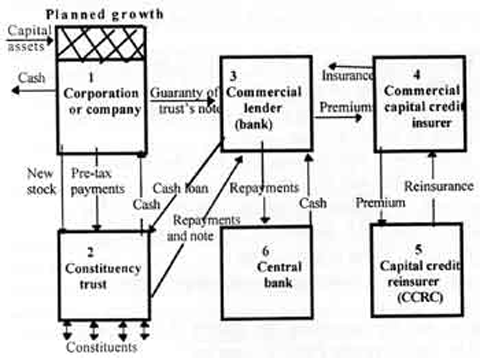

Consider the following diagram which can be used to open individual capital ownership to anyone:

A big corporation or company wishes to expand. It could go to the bank for the money but, if it were much cheaper, it might decide to ask a Constituent Trust (similar to an ESOP) to put up the cash. Acting for employees or for anyone, the trustees make a proposal to a local bank which independently evaluates the soundness of the proposed expansion. If the expansion is approved, the bank prepares to lend money to the Trust. The Trust gives the money to the corporation and, in exchange, the corporation issues new shares to the Trust which then holds the shares in the name of its constituent clients.

I mentioned cheap money. Well, the present ESOP has some financial advantages, but far from enough. In particular, binary economics proposes that cheap money should be used. Under new legislation providing for low or nil rates of interest for capital expansion linked with wide ownership purposes, the bank would go to the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve would issue the money at a nil or low rate of interest, and give it to the bank which would then lend it to the Trust. (See section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act in the USA.)5

In order to protect the bank and the Trust against possible losses from business failure and default by the corporation, the Trust pays a premium to buy insurance from a Capital Credit Re-insurer. The cost of the premium is added to the cost of the investment and charged to the client, as is the administrative cost of operating the Trust. The financial soundness of the privately owned Capital Credit Insurer will be guaranteed by new legislation creating a Federal Capital Credit Re-insurer (similar to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation — “FDIC” — which safeguards bank deposits against loss).

For the next 5 – 7 years, on average, the Trust will receive dividend income from the stock held in trust for the client. This income is credited towards the cost of the stock bought in the client’s name and is repaid to the local bank which provided the original loan.

The local bank, upon receiving repayment from the Trust, in turn repays the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve can, of course, then cancel the money or recycle it into further industrial expansion by lending it to other banks dealing with other Constituent Trusts acting on behalf of other clients.

As each share of stock is paid for in full, it is released from the Trust and full ownership accrues to the client. He/she will thereafter receive the cash income from his/her investment in the form of dividends or capital appreciation. The money is his or hers!! Although, of course, it is possible to arrange things so that the money is held on trust for the client, if that is appropriate.

The result of all this is that the client becomes the independent owner of a capital estate providing income.

See Binary Economics: The new paradigm by Robert Ashford and Rodney Shakespeare published by the University Press of America.

___

*Final version of paper presented at the ISSEI Conference, Bergen, Norway, Section IV, Workshop 452, August 14-18, 2000. © August 2000, Rodney Shakespeare. Published with author’s permission by the Center for Economic and Social Justice, Washington, D.C.

For further information regarding this paper, contact the author at:

11, Charman House, Hemans Estate, London, SW8 4SP, United Kingdom.

Email: rshakes@globalnet.co.uk